Dr Iyad Al-Attar grasps the nettle – air quality issues in schools

Education enables upward socio-economic mobility and is a key factor to escaping poverty and achieving social cohesion. It creates opportunities to teach values, build confidence and encourage critical thinking to approach the world with well-rounded perspectives. When people acquire knowledge, they establish a knowledge-based track to attain promising economic and social standings. Education is a potent tool to drive innovations and empower the nation’s economy, so citizens can aspire to decent employment and dignified retirement. Education is the bridge the poor need to cross to become middle-class, and onward to financial independence, so they, too, can help others depart from poverty. Well-protected and equipped facilities are essential for providing a suitable learning environment, so nations can have the capacity to dream and reach their destinies.

Learning opportunities and the vicious cycle of poverty

Poverty is a vicious cyclical trap, and education, economic empowerment and a robust healthcare system are required to rise above it. No one can learn in deprivation or illness, as both impede learning progress. Ultimately, access to food, clean air and water, sanitation and functional educational facilities will grant children healthy platforms for better living and learning, and the quality of air to which students and staff are subjected to is paramount.

School air quality impacts students’ learning, performance, focus, memory and health. Our children spend most of their time learning, studying and exercising in indoor school spaces. Typical selection criteria for parents range from the quality of education to the school’s reputation and proximity to their neighborhood. However, hardly any parent questions the air quality their children inhale. For example, would a higher tuition fee implicitly mean the air quality is better? Does the wellbeing of students hang in the balance of owners of schools, boards of directors and teachers? Should students with limited means inhale poor air quality, simply because better air quality is made available only to the elite? Is inhaling air with suspended particulate matter, VOCs, radon, SOx, and NOx an allowable sin, simply because no authority asks about IAQ for schools before they license them?

Governed by policies, driven by passion

Dr Iyad Al-Attar

To guarantee clean air delivery in schools and air quality, schools should be governed by policies and programmes. Aspiring for the best air quality outcomes is possible if we can effectively position the technologies and innovations that we possess. The most critical realignment is deploying reliable air quality sensors to facilitate continuous monitoring, whereby reliable data are collected and interpreted to take appropriate mitigation action. The data acquired should be shared with the entity in charge, whether it is the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), local municipality or the Ministry of Education.

The premise of this game-changing approach encompasses a blend of command-and-control as well as market-incentive legislation. When a school adheres to legislation driven by concern for IAQ, then its license is renewed, and it is permitted to receive students in classrooms. If they go the extra mile and achieve a better-than-required air quality among community schools, they can be deemed eligible for tax credits, interest-free loans and rebates on retrofitting work, where not only the government can participate in the incentive programmes but so can banks and the private sector.

Undertaking major realignments to alter conventional practices requires better governance to raise the bar with regard to outdoor and indoor air quality. An appropriate mitigation approach must consider multi-disciplinary air quality issues, such as filtration, ventilation, fit for human occupancy variation and relevant system selections.

Complex exposures and interactions of various pollutants

School air quality is further challenged when students are asthmatic or suffer from other chronic respiratory illnesses. The formidable challenge during the pandemic was the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, where filtration technologies and HVAC systems’ performance fell under the analytical knife. Rushing into sweeping conclusions further blurred the vision of addressing the pressing issues of deteriorating air quality. Achieving the best air quality in a given indoor space is like chasing moving targets, which requires considerable expertise to manage the underlying parameters, some of which are time-dependent. Therefore, it is critical to realise that filtration is not a panacea, and, in several cases, involving other technologies is necessary to reach the desired air quality outcomes. However, inappropriate usage of filtration technologies can be counterproductive, as sources of pollution and the physical and chemical characteristics of pollutants can vary, given the applications and challenges to be tackled.

Another aspect often overlooked is the wellbeing of teachers and staff; their health and safety are equally important and should hang in the balance of the air quality equation. Architects and HVAC engineers should be mindful of the appropriate student occupancy, given the volume of indoor space occupied, size of HVAC equipment, required filtration and the type of activities involved. It is also critical to realise that appropriate air quality measures may differ from one school to another and from the classroom to other indoor spaces. This highlights the importance of bespoke air quality and filtration solutions, accompanied by adaptive HVAC system selection, performance and operation. Furthermore, the number of students and their activities could vary, whether in a classroom, gym or auditorium. The essence of serving a purpose is realising its objectives. No one would want to send their loved ones to dusty, stuffy and smelly schools. Ultimately, air quality realignments should investigate critical considerations such as the health effects of complex exposure to various solid and gaseous pollutants.

The knockout of the pandemic

To further scar a tangled education situation, unprecedented disruption through school closures was a knockout[1]. The United Nations said closures of schools had impacted 94% of students worldwide, putting close to 1.6 billion children and youth out of school by April 2020[2]. The pandemic forced students to abandon their classrooms, which is nearly a declaration that their indoor space is thought to be occupied by SARS-CoV-2 and, therefore, unfit for healthy educational purposes.

Figure 2: Many classrooms were abandoned during the pandemic

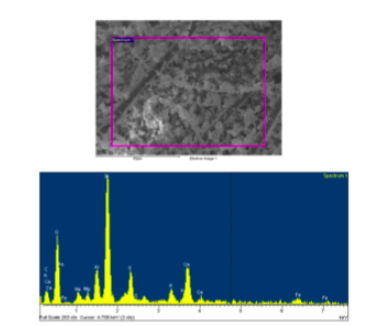

The return to physical attendance brought tremendous controversy relevant to the fitness of schools to reopen their classrooms. Protecting the wellbeing of students emerged as a requirement to reopen, and facility managers relied on maintenance measures and mask-mandates as primary measures for business-as-usual status. Unfortunately, the pandemic was treated as a business opportunity rather than a litmus test for realignments. In fact, during the pandemic, the focus was merely on SARS-CoV-2, overlooking the entire spectrum of pollutants that, for decades, got us ill and took many lives. Examples range from Particulate Matter PM1 (Figure 3) to various VOCs, particularly formaldehyde, radon, NOx, Sox, ammonia and CO2. The sad truth is that the main focus for years was on the capture of solid particles, neglecting other pollutants, such as gases and bioaerosols. Furthermore, identifying the sources of indoor pollutants is essential to employing appropriate mitigation and possible filtration upgrades.

Figure 3: Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis of sample air filter taken from a school

Meeting challenges

Nothing speaks louder than advocating for a decent education that could change the world for children, communities and societies. Education is the lens through which we can preserve our planet from the rising tides of air pollution and, eventually, climate change. Education levels the playing field among global societies and grants everyone the chance to contribute. Therefore, providing healthy, pleasant and sustainable learning environments for everyone is critical to meeting our future challenges.

The rising tide of atmospheric pollution constitutes one of the major problems in urban areas and, particularly, in schools. Adverse health effects from exposure to airborne pollutants have highlighted the importance of better air quality in classrooms and the impact on students’ performance[3-6].

Conclusion

Educational challenges are trans-boundary, and how to deal with them impacts our current and future prosperity. Therefore, it may be time to reimagine the educational landscape and focus on how teaching and learning are structured and delivered, with indoor and outdoor air quality being significant considerations. Let us seize the opportunity to redo the math and orchestrate new ways to address how we perceive and conceive the possible changes in the school’s built environment. The right of students and staff to inhale clean air in their facilities cannot be denied by those who adhere to yesterday’s toolbox. The fundamental change we require lies in unlearning conventional maintenance practices and embracing relevant technologies and innovations to raise the bar on air quality. Before we ask for the price of enhancing air quality, we should design the promise of rendering our educational facilities fit for purpose. In that case, we should listen carefully to the creaking sounds of the conventional HVAC systems as they send a hidden message about their inability to deliver the air quality desired by occupants. Facing the imminent winds of change with a furrowed brow cannot be enough; we either take a chance or take charge of our environmental challenges.

References:

[1] UNESCO Institute for Statistics. “Combining Data on Out-of-School Children, Completion and Learning to Offer a More Comprehensive View on SDG 4”, 2019. Ref: UIS/2019/ED/IP/61 © UNESCO-UIS 2019. http://www.uis.unesco.org.

[2] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). COVID-19 and human development: Assessing the crisis, envisioning the recovery. 2020 Human Development Perspectives, 2020, New York: UNDP, available at http://hdr.undp.org/en/hdp-covid.

[3] Annesi-Maesano I, Baiz N, Banerjee S, Rudnai P, Rive S, SINPHONIE Group. Indoor air quality and sources in schools and related health effects. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2013;16(8):491-550. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2013.853609. PMID: 24298914.

[4] W.J. Trompetter, M. Boulic, T. Ancelet, J.C. Garcia-Ramirez, P.K. Davy, Y. Wang, R. Phipps, “The effect of ventilation on air particulate matter in school classrooms, Journal of Building Engineering, Volume 18, 2018, Pages 164-171, ISSN 2352-7102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2018.03.009.

[5] Tunga Salthammer, Erik Uhde, Tobias Schripp, Alexandra Schieweck, Lidia Morawska, Mandana Mazaheri, Sam Clifford, Congrong He, Giorgio Buonanno, Xavier Querol, Mar Viana, Prashant Kumar, Children’s well-being at schools: Impact of climatic conditions and air pollution, Environment International, Volume 94, 2016, Pages 196-210, ISSN 0160-4120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.05.009.

[6] Pradeep Kumar, A.B. Singh, Taruna Arora, Sevaram Singh, Rajeev Singh, Critical review on emerging health effects associated with the indoor air quality and its sustainable management, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 872, 2023, 162163, ISSN 0048-9697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162163.

Copyright © 2006-2025 - CPI Industry. All rights reserved.