Imran Ahmed, Senior Mechanical Engineer of the Engineering and Maintenance Department at Al Qassimi Hospital, talks about the different projects in progress at the Sharjah-based facility run by the UAE Ministry of Health & Prevention, as it prepares to apply for JCI accreditation.

Imran Ahmed

The hospital is said to be undergoing several changes at present. Could you share details of what those changes are and the objectives behind them?

Until last year, we did not have the necessary systems in place to control the temperature – or even the air flow – inside the hospital. And there are certain areas here where temperature control is crucial, one being the pharmacy. A certain temperature has to be maintained to keep medications in safe zones. To address that, we have started a new project that involves us collaborating with a company that supplies the kind of systems we need to control temperature and air flow.

It’s not rocket science what they are doing, which is providing butterfly valves for our AHUs. But, rather than fixing the controls in the plant room, they are connecting them to the VAV inside each zone. Being a running hospital, we can’t do it for each room, like how you would have it in your house or in a new building being constructed. We face more challenges, because we have critical services running – we could not just shut down departments or locations. Also, the project value would have gone up five times if we had chosen to pull multiple cables into every room.

We, therefore, decided to go into control zones. We are assigning, say, four rooms as one zone and setting up controls within that area. Since we also have sharing rooms, we are seeing to it that we design everything in such a way that will ensure maximum comfort for the patients.

For this project, we have finished a pilot involving our administration area, which proved to be successful. So that’s basically how we started. Of course, we first tried to analyse what challenges we would encounter. When we saw that the whole thing was feasible and that any resulting downtime would not affect patient comfort – that was when we thought: Okay, this is good. We need to apply this to all our patient units.

We only had one coil for our chilled water supply. We had chilled water circulating in one coil, and hot water circulating in an adjacent coil

As you mentioned, you’re just starting this project. How did you deal with temperature control before?

Our methods were quite conventional. With our AHU design, for example, we only had one coil for our chilled water supply. We had chilled water circulating in one coil, and hot water circulating in an adjacent coil. Now, in the case of a complaint from one department about it being too cold, the technicians would respond by opening the hot water valve, to allow hot water to circulate.

Can you imagine how much energy was being wasted? Also, we could not play with the chilled water supply too much, because it is all a branch; it is all connected to the other AHUs. Maybe you will have one department feeling hot and another feeling cold. But then again, opening the hot water valve was the easiest option we had. And it was a hit-or-miss strategy. We had to keep checking with people. Are you feeling comfortable now? Is the air temperature fine? Like I said, it was all a case of hit-or-miss. For the past 30 years, that was the practice. But now, I guess you can say that we are at a development stage. We are improving and have undertaken projects that will put us on the same page as other hospitals.

Did you have a “model” hospital or hospitals in mind? Did you look into what others were doing?

We did. We started out by looking at hospitals like Abu Dhabi’s Al Mafraq Hospital. We specifically established relationships with the Al Mafraq team and got as much information as we could, because the two hospitals – Al Mafraq and Al Qassimi – have many similarities, including age and the kind of services they offer.

This went on for about three years, during which we tried to understand how they were developing and facing challenges. But Al Mafraq wasn’t the only hospital we studied. We also referred to a number of European hospitals that were following JCI (Joint Commission International) standards. JCI has been a topic of discussion for us for the past six or seven years. We’ve been trying to determine if we could earn JCI certification for all MoH hospitals. In fact, the plan is to have all MoH hospitals JCI-certified by 2020. It’s our mission, and something we’re aggressively pursuing.

This went on for about three years, during which we tried to understand how they were developing and facing challenges. But Al Mafraq wasn’t the only hospital we studied. We also referred to a number of European hospitals that were following JCI (Joint Commission International) standards. JCI has been a topic of discussion for us for the past six or seven years. We’ve been trying to determine if we could earn JCI certification for all MoH hospitals. In fact, the plan is to have all MoH hospitals JCI-certified by 2020. It’s our mission, and something we’re aggressively pursuing.

December this year will be the initial visit, during which the JCI committee will inform us if we are ready to apply for accreditation. It is owing to our anticipation of the visit that everyone here in the hospital has not been getting much sleep. We are right now renovating around six departments to make sure that they comply with design standards, in terms of providing services, like clean utility and dirty utility, and making certain that isolation areas have anterooms.

Presently, we already have 12 isolation rooms, a project that we only completed six months ago. We are monitoring the isolation rooms with negative pressure, as well as labs and other rooms with positive pressure. We are making sure that the hospital staff members understand why certain environments need negative pressure, while others need positive.

How is this mission to earn JCI accreditation affecting MEP and maintenance work in the hospital?

I can’t give you the exact numbers, but I’m quite certain that 70% of the JCI work required in the hospital is related with MEP services. In its standards, for example, JCI stresses patient safety. Now, patient safety is just one bullet point, yes? Not exactly, because you can expand it, elaborate on it. Look deeper, and you’ll realise that it means having effective and reliable alarm and fire-fighting systems, and having a good evacuation plan and exit strategy. It means fire drills are regularly conducted.

I’m quite certain that 70% of the JCI work required in the hospital is related with MEP services

It’s one simple point that brings so many projects into play, resulting in the expansion of my role as head of the Maintenance and Engineering Department. My role is not confined and comes with the challenge of not only providing all required services but also maintaining them and making sure that they are tested before they are run.

Take laboratory services, for example. If the lab team sees that JCI standards require them to have a cold-store monitoring system, they won’t go to anyone else but me. And if the cold-store temperature is supposed to be within the limits of, say, 2-5 degrees C, they may come to me saying, “JCI says monitoring should be done.” The challenge for me then would be how to make the monitoring process effective. How can we make it work for us? Do we have someone who can check the cold store every two hours? What do we do?

With a monitoring system, we can keep track of the temperature. The system will also keep a log, and if temperature goes below the set limits, we will immediately get a message either through SMS or email, saying that a particular cold store is out of the required temperature range and needs to be checked. It has happened in the past that, owing to overloading, there was an electrical power trip.

Unless I am in the area or someone notifies me of the problem, I wouldn’t know. Imagine how disastrous it would be if that happened and you have millions worth of reagents stored outside of the temperature range for hours. The reagents would be destroyed.

Unless I am in the area or someone notifies me of the problem, I wouldn’t know. Imagine how disastrous it would be if that happened and you have millions worth of reagents stored outside of the temperature range for hours. The reagents would be destroyed.

It’s become clear to us that having a good monitoring system in place is critical. Now, we are working on automating our processes, because even if you have the extra manpower to do regular checks, there’s always room for human error. We’ve experienced losses due to human error, and when those losses add up, they are more than what it would cost us to automate our processes. We have, in fact, already purchased a cold-store monitoring system, but we have yet to install it because there’s still renovation work going on in the lab. We’ll put the system to use as soon as the lab is functional.

A similar scenario involves our cath lab (catheterisation laboratory). We have these special medical-graded fridges. They maintain temperatures of 2-4 degrees C, which is very critical, because they store equipment used for catheterisation or operations. We’re talking about very expensive equipment.

One time, there was a power failure, and it happened late at night, so no one realised. By morning, when people arrived for work, they realised the fridges were off. They switched them back on, but it was too late. We’d already lost equipment worth thousands of dirhams. Immediately, we set about getting alarm systems, but they were not enough, because someone has to be present to hear the alarm and notify us. We decided to go even more advanced. We looked into online systems that would notify us through a call or an SMS every time a fridge was going out of temperature range.

It was always a case of no one willing to take responsibility for such critical work

The system has been installed and is now running. It comes with a special UPS battery. The fridge is already getting power from a UPS supply, but it’s always good to have a backup.

How did you monitor your cath lab equipment before you installed the new system?

I had to send technicians every two hours, and we had to keep a log chart. But there was always a disagreement over whose responsibility it is. Is it the responsibility of my FM contractor? But the FM contractor would say it’s not, because he doesn’t handle medical equipment. Then it would go to the medical or biomedical engineering department, but they would say monitoring is not their responsibility. They would tell me that if there’s a problem with the system, then they would come to fix it. So then it would go to the staff. But the staff is not available 24/7. It was always a case of no one willing to take responsibility for such critical work. Also, the technicians keep changing, and these technicians are juggling multiple assignments. Imagine the assigned technician getting caught up in one task and not being able to check the equipment. What if a problem comes up during that period? Would you hold the technician responsible? That is why automating the system seemed like the safer, more sensible option for me.

I understand the hospital has also replaced its chillers.

That’s right. The chillers that we replaced were 35 years old and were running fine. The only problem was that the refrigerant is no longer available.

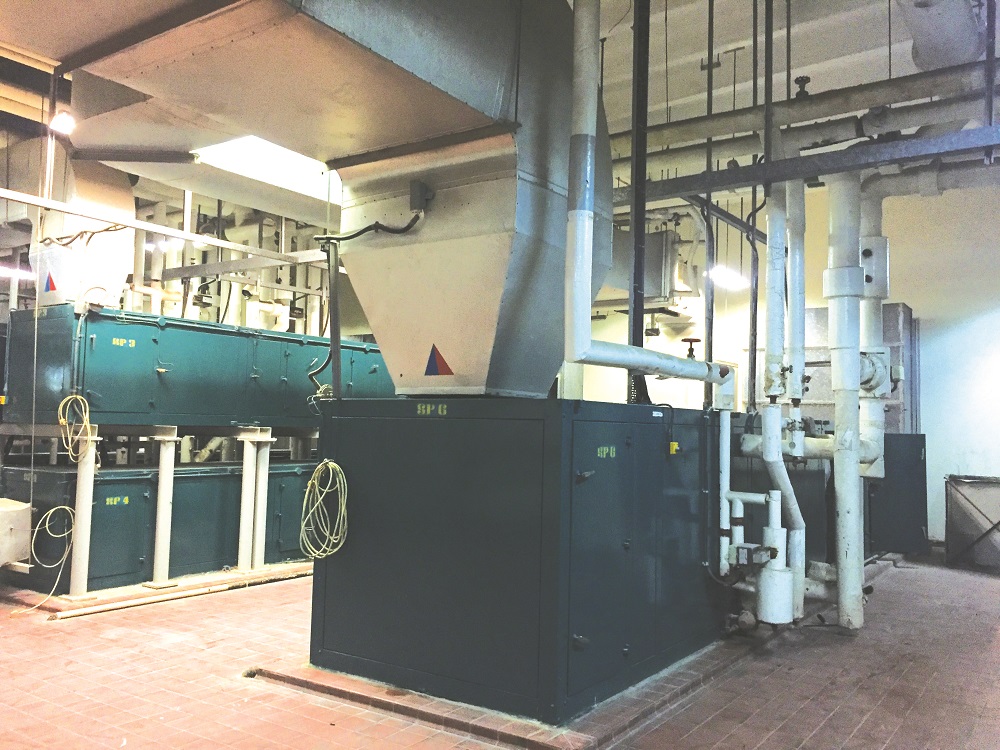

Al Qassimi Hospital plant room

When I was given the Al Qassimi assignment in 2013, I evaluated the life of all HVAC equipment. I prioritised this because any equipment failure, especially in our kind of weather, would mean disaster. And I didn’t want to take the risk of continuing with equipment running on a refrigerant that was no longer available. Also, the manufacturer of the old chillers had stopped offering us support, because they said they were out of the water-cooled business. I think there was also a change in their management structure, which complicated things. Anyway, since I was not getting support from them, I decided that it was time for a change.

What was the refrigerant of the old chillers?

R-11, which has been banned by the government. The new chillers use R-123, designed by the chiller manufacturer especially for its water-cooled chillers.

To avoid encountering the problem I had with the old chillers, I made sure that our deal with the manufacturer included a lifetime supply of the refrigerant.

But regulations on refrigerants are changing, with certain gases, including R-123, scheduled to be phased out.

Yes, but it’s still allowed. It’s not banned yet, and so as of today, I don’t have a problem with R-123. We’re looking at, say, 20 years down the line. Until then, we can use it. There’s really not much option left. Even R-134 has been phased out in Europe. What is left now? I mean, anything you choose, after a few years, they will say it is not feasible. We have package units that use R-410A, which has a high efficiency. But it’s very expensive. Few companies are selling it, so you’re paying too much for the gas.

How have the new chillers benefited the hospital? Have you noticed improved energy-efficiency levels?

I have been gathering data on electrical efficiency. As of the three-month data that I have collected, I have found that with the new water-cooled chillers, the hospital’s electrical consumption from April to July has dropped by 65%.

I didn’t want to take the risk of continuing with equipment running on a refrigerant that was no longer available

Yes, we have saved 65%. It’s because, first, the refrigerant we have is very efficient. Second, the old systems were constant-speed, while the new ones are variable-speed. Third, the new chillers are governed by an intelligent system, called CPM (Chiller Plant Manager). The CPM decides which chiller needs to take how much load. Even if the load in the hospital is, say, 60%, it would run two units based on its requirement. It would distribute the load 30-30, and it would make sure that the system is balanced and running within its parameters. Running one chiller at 100% would not give you the same electrical efficiencies that running two at 50-50% would give you. And the life of the chiller itself would be in a much better state. So I have three units, two running and one on stand-by. This is how the system has been designed. If the cooling load is less than 40, then I would have only one chiller running, two on standby.

Even our cooling tower has been updated. Before it was constant speed, but we now have VFDs installed in our motors, and our pumps are highly efficient. So, a lot of changes have been applied, and we have found that they are for the better.

I have heard it said that hospitals live and die by their infection rate. What measures have you introduced to ensure good air quality and prevent the spread of infection?

We have an infection control department, of which I am a member. I provide them with services related to utility-based infections, like water analysis and water-quality analysis. We are carrying out aggressive action plans to prevent or counter hospital-acquired infections, an example of which is cleaning and disinfecting the ducting system.

Al Qassimi Hospital’s new water-cooled chiller

We had a case in the past when we noticed that the infection rate in one ward was slightly going up, with the bacteria seeming to be moving from one location to another. We investigated and came to the conclusion that it could only be moving through the air supply. So immediately, I proposed that we disinfect the ducts, because they seemed to be the only link between the two locations, and fortunately, that resolved the problem.

Government regulations mandate that ducts have to be cleaned regularly, but it is often neglected. It could be owing to the challenge with cleaning the ducts – you need to empty the location or area. In hospitals, that is difficult, because you’ll rarely find patient wards empty, and it’s not easy moving patients to other locations.

But regular duct cleaning and disinfection are necessary, and so with our current FM contractor, I stipulate in my contract with them that they need to clean the ducting of three departments every year. My FM contractor even brings in a specialised company that utilises robots to clean the ducts, especially the areas that a person can’t reach.

Any other issues or challenges in the hospital that you are facing?

Challenges within the hospital are many, but what I do is identify those that I can address within a certain amount of time. At present, I need to provide additional power to our hospital, because our transformers are pretty old, and they are already overloaded. This matter is something I have been working on for the past four months. The good news is I’ve been able to convince the [UAE] Ministry of Infrastructure Development to provide additional two transformers powered by SEWA (Sharjah Electricity & Water Authority).

Apart from that, there are always minor challenges. One is maintaining the air quality in our cardiac operations theatre. There’s a problem with the design itself. Initially, you might think there’s no problem with the temperature, but once the machines and operating lights are switched on or the number of people inside increases, the temperature shoots up.

That’s my next challenge – to replace the AHUs of the cardiac centre. Actually, the challenge is not replacing them. I could get any company to bring in the units. The problem is the size of the ducting. If I’m selecting one AHU, I would have to design the ducting according to that AHU. But if I’m going to increase the size of the AHU, the ducting size will be affected. If I continue to use a bigger-capacity AHU with a smaller-size ducting, what will happen is, initially it would be okay, maybe. But then you will start getting vibrations and sound. There might even be air leakage, because the design of the duct is different from the original set-up. Thus, it’s not an easy task for me to just replace the unit. It is more than that. We have to study the ducting itself. Do we need to change the duct? If we need to change the duct, that will mean basically shutting down the cardiac building. We have to shut it down, so we can open the entire roof and change the ducting. Installing new ducts inside an operations theatre is not an easy task, but I’m working on it. Let’s hope for the best.

(The writer is the Assistant Editor of Climate Control Middle East.)

Copyright © 2006-2025 - CPI Industry. All rights reserved.