How do you fancy your pool – hot, tepid or cold? The Romans plunged into all three and created the concept of saunas, chilled piped water and refrigerators.

That the ancient Romans kept their villas warm with hypocausts or underfloor furnaces – an early forms of central heating – is common knowledge now, at least to those who read about it in the last issue of the magazine or elsewhere.

That the ancient Romans kept their villas warm with hypocausts or underfloor furnaces – an early forms of central heating – is common knowledge now, at least to those who read about it in the last issue of the magazine or elsewhere.

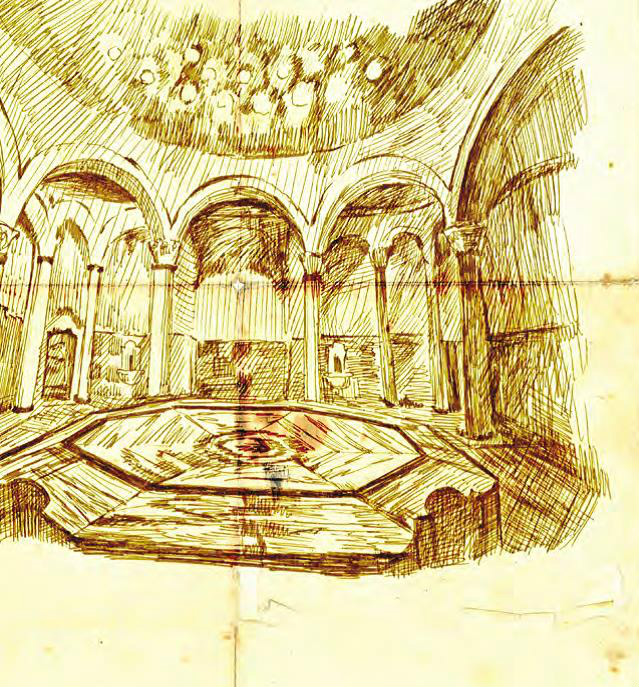

The Romans took this luxury a step further with their public baths or thermae. These were no ordinary bathhouses where a weary traveller grabbed a quick shower on the go. They were recreation complexes, whose portals only those with time and money on their hands entered.

The discerning client first passed through the atrium, or the main entrance, where the young hung out and the elderly hobnobbed.

[div class=”text-box text-box-left”]

While it was relatively easy to figure out how to maintain a steady supply of piped hot water and steam through a building, keeping the water cold in the frigidarium was a more tricky business.

In the absence of modern-day artificial cooling methods, the Roman frigidariums were kept cold naturally. The structures were built with marble floors, high roofs and small windows to maintain low temperatures. The water was also kept cold by using snow in winter.

Another natural form of air conditioning was to use solar heat to eject the hot air from the chamber. A large pipe was embedded deep into a covered trench outside, leading to the bathhouse. The pipe had holes to drain the water that condensed inside. The end of the pipe entering the house would act as the source of incoming air, with a chimney on top.

The sun would heat up the chimney, causing the air inside to rise, in the process drawing air through the pipe. Since the cool air was drawn in from the pipe buried deep underground, it was unaffected by the ambient temperature, either in summer or winter. Interestingly, cooling would actually be provided by the thermal mass of the earth around the pipe. All that the solar heat did was pump the air. Note that no F-gases were used.

[end-div]

After unwinding with light exercises and exchanging pleasantries with fellow-clients, the bather went into the apodyterium or the changing room. Then began the elaborate bathing ritual, first with a dip in the caldarium. A caldarium (made of two Latin words, caldus meaning hot and arium meaning place) was an area with a hot plunge-bath, devised to open the pores of the skin and cleanse the body.

The bather would, then, languorously slosh about in warm water in the tepidarium. Tepid, of course, means lukewarm. The area was designed to prepare the body for the frigidarium – a cold plunge-bath – to close the pores, leaving the bather refreshed and literally chilled out.

However, on the way, if the bather so fancied, he (or she, for there were segregated bathing areas for women with separate timings), could saunter through a passageway into either the sudatorium – moist steam bath – or the laconicum – a dry steam bath – much like modern-day saunas, that induced further sweating and cleansing. A workout in the adjacent gymnasium or enjoying an aromatic oil massage before the final cold bath were other options. If one was not sated with the array of baths with varying temperatures and wet and dry saunas, there was the natatorium – a regular swimming pool with normal temperature. (Natatus means swimming in Latin).

One could also escape into a library, take a leisurely stroll in the gardens or relax in picnic, entertainment, food court or shopping areas, much like our malls.

Apart from being centres for socialising, networking and exchanging gossip, the Roman baths offered a rejuvenating health spa treatment with piped hot and chilled water systems ensuring thermal comfort everywhere. District Heating/Cooling in its naissance?

Apart from being centres for socialising, networking and exchanging gossip, the Roman baths offered a rejuvenating health spa treatment with piped hot and chilled water systems ensuring thermal comfort everywhere. District Heating/Cooling in its naissance?

This is how it worked…

The great Roman bathhouses were heated using hypocausts, with hot water and airflow systems connected by ducts, consisting of stone or brick tunnels under the floor or through wall cavities. Hot gasses could escape through wall chimneys.

The wet sauna room had a pool of water heated by the same fire from the hypocaust, making it energy efficient. The water was heated in huge kettles and piped to different rooms with varying temperatures as required.

[div class=”text-box text-box-left”]

Ondols or heating systems excavated in Korea dating back to circa 1000 BC also used the underfloor heat transfer method similar to Roman hypocausts, but channeled heat from wood fires used for cooking.

[end-div]

The bath buildings had two floors, with the saunas built directly above the furnace or source of fire. The caldarium with the hot-water plunge came next, with the tepidarium with water placed away from direct heat to keep it lukewarm. The tepidarium also insulated the hot rooms from the cold rooms, which were on the top.

The water for the baths came from rivers or streams nearby or from afar through aqueducts. The baths were also located close to hot water springs, and tapped into geothermal energy.

The writer is the Associate Editor of Climate Control Middle East. She can be reached at pratibha@cpi-industry.com

Copyright © 2006-2025 - CPI Industry. All rights reserved.