“If nothing changes, we are heading towards a 2.8 degree temperature rise – towards a dangerous and unstable world with horrendous heat with horrendous effect,” was the outcome of the global ‘shock-taking’, during the Climate Ambition Summit, in New York, points out Dr Rajendra Shende

History was made eight years ago. The global cooperation under multilateral environmental agreements took a turn when the Paris Climate Agreement was signed in 2015. That moment will go down in history as a unique case study on how the United Nations leveraged its convening power to get all 196 countries in the world under one roof to seek and explore a collective solution to the planetary crisis. Though it is known well that the global climate crisis is caused mainly by the rich countries – predominantly developed countries – due to their indiscriminate consumption of fossil fuels, both developed and developing countries, and even the least developed countries, agreed to take action to reduce the use of fossil fuel without differentiated timetables. Earlier global agreements – for example, the Montreal Protocol – aimed at protecting the Ozone Layer, stipulated that developed countries would take action first and that developing countries would follow suit.

Indeed, before the Paris Climate Agreement, the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 had adopted such a differentiated timetable. The reduction in emissions was to be led by developed countries, who were historically responsible for the majority of the emissions.

The unprecedented collective commitments, in the form of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), were then provided by each of the developed and developing countries under the Paris Climate Agreement. That heralded the possible era of global coalitions to rescue the planet from the climate crisis. Never before had the world witnessed such solidarity by all nations faced with an emergency of a pandemic scale.

Strangely, it is also for the first time in the history of global environmental agreements that even after such a show of global solidarity, the reduction in emissions, the key objective of the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), has not been achieved. After three decades of agreement on the Convention, 25 years after the Kyoto Protocol and eight years after the Paris Climate Agreement there has been no sign of any reduction in the emission of greenhouse gases.

To be fair, however, the Paris Climate Agreement for the first time rightly stipulated cross-checking and stock-taking to assess the progress of implementation of commitments under NDCs. Article 14 of the Paris Climate Agreement stated that the first global stocktake of commitments made by the countries under NDCs would take place in 2023 at COP28, in Dubai, and every five years thereafter. It also stated that the outcome of the global stocktake shall help the Parties to upgrade their NDCs and enhance global cooperation.

COP28 is, therefore, famed as the ‘Global Stock-taking COP’.

The objective of the Global Stock-taking is to assess the progress under the Agreement, particularly in meeting short- and long-term goals. The UNFCCC Secretariat has formed a special expert group for data analysis, received from the countries and other agencies, so that a consolidated report could be discussed at COP28 to enable countries to update their NDCs. The elements of Global Stock-taking in COP28 were very well defined during the time of the Paris Climate Agreement itself. They include, inter alia, mitigation levels achieved by each country, adaptation efforts made at national level and climate finance provided to the developing countries by the developed countries.

Unfortunately, the Global Stock-taking exercise will be taking place at the time when the world is fractured and conflict-torn. The focus of the world leaders is more on geopolitical greed than ecological need. ‘Fundamental reforms’ and ‘Complete Overhaul’ of the global multilateral system, within which the United Nations and international financial institutes operate, have been discussed by all the world leaders, but they have remained wishful thinking.

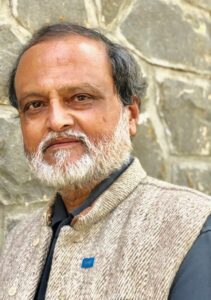

Dr Rajendra Shende

The good news is that weeks before COP28, world leaders had key opportunities to develop alliances and strategies to deal with the ‘climate pandemic’. The key reports that matter to all the governments were released well before the vital meetings of power groups, like G7, BRICS and G20. The Climate Ambition Summit, on September 20, 2023, convened by the UN Secretary-General, as part of the 78th UN General Assembly, also benefitted from these reports. The IPCC’s ‘Synthesis Report of AR6’, in March 2023; the World Meteorological report, titled ‘Global Annual to Decadal Climate Update’ of May 2023; the ‘United in Science 2023’ – a multi-agency report, coordinated by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) of Sept 2023; and the report that matters for Global Stock-taking, called the Synthesis Report of the Technical Dialogue on the first Global Stock-taking, coordinated by UNFCCC, were all available for countries in time to strategise on a climate solution.

The Synthesis Report of the Technical Dialogue lists 17 findings that highlight shortfall in emission reduction, adaptation measures and the gap in financing from developed countries to the developing countries, so crucially necessary for the latter’s emission mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage mitigation efforts. These findings point out that the planet is on a downward spiral and that the window of opportunity to take action is fast closing.

The key findings are:

· Based on current NDCs, the gap in emissions, consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C in 2030, is estimated to be 20.3-23.9 Gt CO2 eq. So, the current global emission that continues to rise without any sign of abatement – except for a small dip, observed during COVID-19, when the world literally came to halt – is about 55 Gt CO2 eq.

· Global emissions have not yet peaked. They need to peak between 2020 and 2025, as per IPCC AR6, to limit warming to the Paris Agreement temperature goal. All Parties need to undertake rapid and deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in the decades after peaking

· Much more ambitious targets in NDCs are needed to reduce global emissions by 43% by 2030 and, further, by 60% by 2035, compared to 2019 levels and reach net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050, globally.

· Achieving net-zero CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions requires scaling up renewable energy – as per IEA, tripling the generation from renewable sources – while phasing out fossil fuels; ending deforestation; reducing non-CO2 emissions, like HFCs, from cooling systems and methane from refineries.

The WMO’s report, ‘United in Science’ stated that the “planet is far off track from meeting its climate goals. This undermines global efforts to tackle hunger, poverty and ill-health, improve access to clean water and energy and many other aspects of sustainable development”. The most fearsome statement came from WMO reports that the annual mean global near-surface temperature for each year between 2023 and 2027 is predicted to be between 1.1 degrees C and 1.8 degrees C higher than the 1850-1900 average. There is a 98% chance of at least one in the next five years beating the temperature record set in 2016, when there was an exceptionally strong El Niño.

So, where do we go from here? That exactly is what COP28 in Dubai is all about.

Sarcasm is not intended, but as Global Stock-taking continues, humanity is facing global ‘shock-taking’. The intensity and frequency of climate disasters are escalating without any signs of waning. From Algeria to Australia, from Bulgaria to Brazil, from Croatia to California and from Hunan to Hawaii, the wildfires continue to spread, aggravated by higher temperature. The effect of El Nino, which should have started much later in the year, has entered the disaster zone much earlier and may stay longer. From the Arctic to the Antarctic and from the Himalayas to the Swiss mountains, the glaciers are melting.

The United States of America, the richest country in the world, has set a new record for billion-dollar climate disasters in a single year. As of September 11, 2023, the country has experienced extreme weather events, costing USD 1 billion or more already this year, passing the previous mark of 22 disasters, in 2020. There were 81 weather-, climate- and water-related disasters in Asia in 2022, of which over 83% were flood and storm events. More than 5,000 people lost their lives, more than 50 million people were directly affected, and there was more than USD 36 billion in economic damages, according to the WMO report.

The G7 meeting in April, the BRICS summit in August and the G20 summit in September were timely opportunities in 2023 for countries with more than 80% of greenhouse gas emissions to develop emergency plans and draw battlelines against the common enemy of climate change. Unfortunately, the developing and drawing did not happen. The closest the countries came to such a much-needed strategy was during the G20 meeting, where they agreed to pursue the tripling of renewable energy capacity globally by 2030, as recommended by the International Energy Agency, and accepted the need to phase-down unabated coal power, but stopped short of enhancing the much-needed climate efforts, as per the reports released in 2023. All these meetings successfully avoided naming and blaming Russia and Ukraine but could not succeed in naming and blaming those developed countries responsible for not providing promised climate finance of USD 100 billion, annually, starting from 2020.

“If nothing changes, we are heading towards a 2.8 degree temperature rise – towards a dangerous and unstable world with horrendous heat with horrendous effect,” was the outcome of the global ‘shock-taking’ in New York, during the Climate Ambition Summit that concluded on September 20. The hungry, burnt, sick and flood-swept world is now waiting for the outcome of Global Stock-taking in Dubai.

The writer is Former Director of UNEP. He is also the Founder-Director, Green TERRE Foundation; Prime Mover, SCCN; and Coordinating Lead Author, IPCC, which won the Nobel Peace Prize. He may be reached at shende.rajendra@gmail.com. He writes exclusively for Climate Control Middle East magazine.

Copyright © 2006-2025 - CPI Industry. All rights reserved.