How to protect pumping systems from damaging pressure surges

Water hammer has the potential of causing significant damage to pumping systems. Most people in the pumping industry have a tale to tell about burst or collapsed pipes, broken or damaged valves, pressure gauges and even pumps. This article looks at ways to prevent damage and extend the life of pumping systems.

The basic of water hammer

The term “water hammer” is used to describe pressure surges within a piping system. There are a range of mechanisms and triggers for water hammer, and having a clear understanding of what is causing the phenomenon in a particular installation is a key aspect to identifying the right solution.

The science in a nutshell

The mechanics of water hammer are actually quite simple.

One cause of water hammer is when the leading edge of a fluid column in a pumping system encounters a blockage, a common example being a suddenly closed valve. When this happens, the flow of the water at the leading edge is instantly halted, but the fluid behind is still moving and starts to compress.

Owing to this compression, a small amount of fluid continues to enter the pipework, even though the water at the leading edge has stopped moving. The kinetic energy of the water in the system is converted to pressure energy as the water compresses. Logically, this pressure energy created cannot continue past the blockage in the system. Instead, the pressure wave generated by the compression of water in the pipe will travel back upstream.

The other primary cause of water hammer is water column separation and closure. This occurs when the column of liquid water within a piping system is separated and, subsequently, closes again, generating a damaging shockwave.

Regardless of the cause, the increased pressure generated by the water hammer phenomenon can cause significant damage to any system not designed to accommodate such stresses, bursting pipes, damaging valves, and more.

This can occur in a two-phase system – one in which water changes state and can exist as both a liquid and a vapour in the same confined volume. This ‘phase change’ (that is, liquid water to water vapour) can take place whenever the pressure in a pipeline is reduced to that of the vapour pressure of the water1.

These causes have a number of triggers. Pump starts and stops can cause water hammer through both mechanisms. A rapid change in flow and system pressure during starting or stopping can cause sudden closure of check valves, while changes in the direction of flow can induce water column separation.

The solutions

Solving the water hammer problem requires either mitigating its effects or preventing its occurrence altogether. To this end, there are a number of solutions to consider when designing a pumping system.

Pressure tanks, surge chambers or similar accumulators can all be used to absorb pressure surges and are useful tools in the fight against water hammer. That said, preventing the pressure surges, in the first place, is often a better strategy.

Controlling valve closure time (prevention)

As discussed earlier, sudden closure of a valve is one of the primary causes of water hammer. Of the many variables at play within a pumping system, valve closure time significantly impacts the likelihood of damaging water hammer occurring, yet is a factor over which we have a level of direct control.

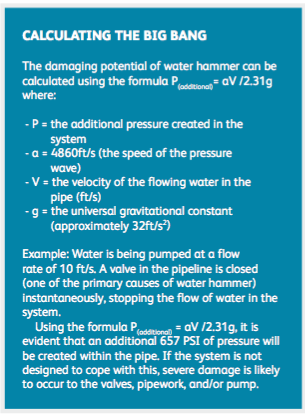

The following equation shows the relationship between valve closure time and the magnitude of the water hammer pressure surge:

The additional pressure generated by the closure of a valve is inversely proportional to the valve closure time. That is, the more slowly the valve is closed, the less significant the increase in pressure will be. Furthermore, it is evident that by careful consideration of the variables within our control (closure time and flow velocity), incidence and intensity of water hammer can be notably reduced.

Controlled valve closure can be achieved manually or by use of motorised valves.

Electronic speed control during pump starting and stopping (prevention)

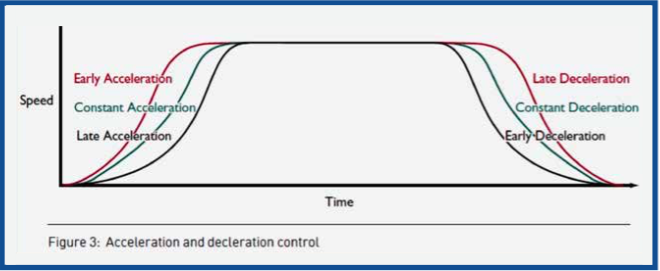

Electronic motor control devices, such as soft starters and variable-speed drives (VSDs) can be used to control the speed of the pump during starting and stopping. This allows for a more gradual increase or decrease in pump speed (and hence of flow and head/pressure) to prevent water column separation, flow reversal and sudden check valve closure.

Controlled starting and stopping of pumps also offers other advantages, including reducing mechanical stresses on the system and electrical supply caused by DOL/ATL/electromechanical starting. This results in reduced maintenance and extended life. Furthermore, soft starters and VSDs can provide a range of advanced motor and system protection functions as well as monitoring and control options.

For example:

What you need to know when using electronic speed control to prevent water hammer

The effectiveness of electronic speed control in the reduction of water hammer is determined not only by the type of technology within the soft starter or VSD (which will be discussed later) but also by the pump and system curves.

System curves

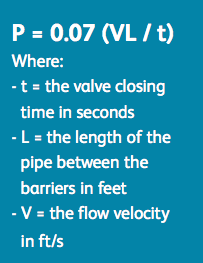

The system curve displays the relationship between flow rate and pressure within the system. It is made up of two components, static head and dynamic head (Figure 1). Flat system curves are more sensitive to changes in speed. A small change in speed will create a big change in flow. This means speed control must be precisely managed to prevent water hammer.

Pump curves

Pump characteristics vary widely, resulting in a range of different possible pump performance curves. With a ‘steep curve’ pump, a large change in pressure produces a small change in flow. Conversely, with a ‘flat curve’ pump, a small change in pressure will result in a large change in flow (Figure 2).

To help abate water hammer in a system, choose a steep curve pump, wherever possible. The relationship between pressure and flow rate for such pumps makes precise control of the flow rate via control of pump speed much easier.

Fixed-or variable-speed control

Once electronic speed control has been decided upon as a solution, next comes the choice between use of a soft starter and a VSD. Both are able to control the acceleration and deceleration of the motor/pump and, thus, mitigate water hammer, so which is the best choice? This will depend on the system characteristics.

Soft starters run the system at full (fixed) speed during operation, controlling the speed during pump starting and stopping only. Once the system reaches full speed, the soft starter is typically bypassed and operates with very high efficiency (losses of less than 0.1%), thus reducing running costs. Soft starters also come at a lower cost than VSDs. Additionally, harmonic generation on to the electrical supply is not an issue with soft starters, meaning they do not necessitate the use of costly filters.

On the other hand, VSDs control pump speed during operation as well as during start and stop. This additional ability to control ‘run time’ speed comes at a cost. VSDs have a considerably higher capital cost than soft starters, often require harmonic filters (costly devices that prevent harmonic distortion on the electrical supply) and, typically, produce energy losses of 4-6%, adding to the lifetime cost of the system. That said, in some pumping systems, the ability to control flow during operation will produce other system efficiencies that outweigh the higher capital and running costs. Unless such system efficiencies are proven to exist, soft starters should be the preferred method of electronic speed control for the mitigation of water hammer.

Soft-start: The importance of acceleration and deceleration control in combatting water hammer

Summary

Water hammer has the potential to cause significant damage to pumping systems. Most in the pumping industry have a tale to tell about burst or collapsed pipes, or broken or damaged valves, pressure gauges and even pumps.

Solving the water hammer problem requires either mitigating its effects or preventing its occurrence altogether. To this end, there are a number of solutions to consider when designing a pumping system, including electronic motor control.

Electronic motor control devices, such as soft starters and variable frequency drives, can be used to control the speed of the pump during starting and stopping. This allows for a more gradual increase or decrease in pump speed, preventing water column separation, flow reversal and sudden check valve closure – a few of the primary causes of water hammer.

Controlled starting and stopping of pumps also offers other advantages, including reducing mechanical stresses on the system and electrical supply, caused by DOL/ATL/electromechanical starting. This results in reduced maintenance and extended life. Soft starters and VSDs can also provide a range of advanced motor and system protection functions as well as monitoring and control options. For example:

Water hammer (pressure surges) occurs from rapid changes in flow. Typically, these rapid changes are associated with start/stopping of pumps and the opening and closing of valves.

Preventing water hammer through control of pump speed:

If flow control can assist overall efficiency, it is advisable to use a VSD; in all other cases, a soft start should be preferred.

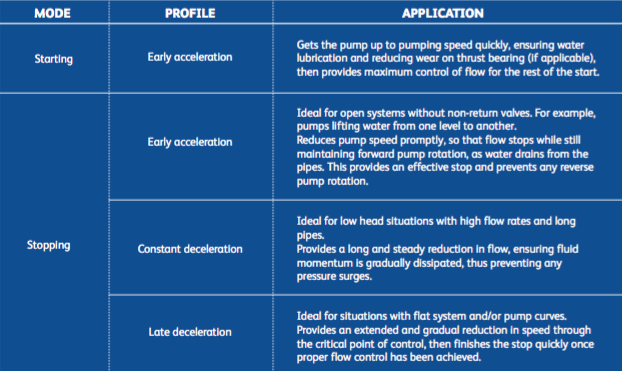

Ensure the soft starter has acceleration/deceleration control and the ability to specify different acceleration and deceleration profiles.

Venugopal Balla is Area Sales Manager at GI Tech. He can be contacted at drives@gitek.ae

_______________________________________________________________________

CPI Industry accepts no liability for the views or opinions expressed in this column, or for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided here.

Copyright © 2006-2025 - CPI Industry. All rights reserved.