A lasting solution to the knotty issue of climate finance is one of the eagerly looked-forward-to outcomes, says Dr Rajendra Shende

“It is not climate change, nor is it climate crisis. It is simply climate collapse.” These were the words of one of my former colleagues from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

He said this just about when he was getting ready to go to the 59th Session of IPCC, from July 25 to 28, in Nairobi, which would begin the process of preparing AR7, the Seventh Assessment Report.

The year 2023 will go down in history as the ‘Year of breaking records’, heat waves across Europe, a month of record-high temperature since record-collection started, the highest marine temperature, the lowest ice cover in the Arctic and the greatest number of high-level meetings on climate change with little impact or output.

The year 2023 started with a heated debate on climate change at a cool place – Davos, in Switzerland, in February. Interestingly, the issues in nearly 12 sessions at the World Economic Forum (WEF) were about economic instruments at the disposal of governments to tackle the climate crisis. “Tax the wealthy companies that make windfall profits and use it to finance the reduction in emission, mitigation,” was the key message in Davos from the friends of The Club of Rome, who first brought the subject of sustainability in global discussions in the 1970s.

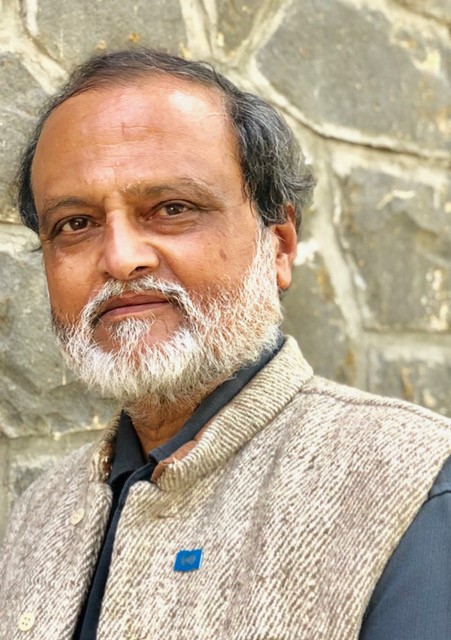

Dr Rajendra Shende

Indeed, nearly 3,000 years ago, when human-induced climate change was non-existent, the taxation system began for societal benefit and soon became a pan-planet framework and solution for economic injustice – that is, to take from the rich to pay the poor. Now, since human-induced climate crisis has engrossed the planet, the tax system is being pushed forward as the way out of formidable challenges, like financing the developing countries for their energy transition to clean energy, for adaptation to climate change, and for mitigating loss and damage incurred due to climate change.

Paying the poor countries for climate damages and for transitioning to a fossil-fuel-free economy, as promised by the rich countries in the last three decades, is now backlogged to more than a trillion dollars. From 2020, the backlog has been increasing at least by USD 100 billion, annually. To top it all is the funding needed for loss and damage cost to be paid by developed countries, as agreed in COP27, in Egypt. The committee constituted has yet to finalise the architecture of that fund. ‘Climate justice’, therefore, remains invisibly unaddressed.

Knowing that ‘financing the climate change’ will be the elephant in the negotiating room during COP28 in Dubai, French President Emmanuel Macron convened the bold initative, ‘Summit for a New Global Financing Pact’, in July 2023 in Paris. The initiative of building a more responsive and inclusive global financial architecture to fight inequalities and to finance the climate transition was the goal of the Summit. Nearly 40 countries and nearly all global financial institutes, including the World Bank and the IMF, participated in the Paris Summit. There was agreement that the ‘obsolete, dysfunctional and unfair’ global financial system needs reforms. There was also consensus that the world needs a roadmap for reforms to address climate change. This, indeed, was the dire need expressed by a number of world leaders much before the Summit. While many leaders commented that one cannot start to ‘reform the system’ when faced with an urgent situation like a fast-spreading pandemic, the world now appears to have got a separate platform to address the issue of climate finance. Whether that would facilitate the negotiations in COPs in the future is something that needs to be seen.

COP28 President-Designate, H.E. Dr. Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber had also received an invitation to attend the Summit – and rightly so. While emphasising the easy availability, accessibility and even affordability of climate finance, H.E. Dr. Al Jaber said, “We need to shift the narrative that views climate finance as a burden and recognises it as an economic opportunity.” This is a potentially inspiring and powerful statement that may set the scheduled climate negotiations in the UAE in perspective.

Firstly, it is an opportunity for developed countries to put an end to centuries-old subsidies for the production and consumption of fossil fuels like coal, oil and natural gas. As per the findings of a research undertaken by the United Nations Development Programme, the world spends an astounding USD 423 billion annually to subsidise fossil fuels for consumers – oil, electricity that is generated by the burning of other fossil fuels, gas and coal. This is four times the amount being called for to help poor countries tackle the climate crisis,

Half of these subsidies are in, and by, developed countries. When indirect costs, including costs to the environment – like the health costs due to pollution by burning fossil fuels, are factored into the subsidies, the indirect cost rises to almost USD 6 trillion, annually, according to data recently published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The backlog of USD 1 trillion promised by developed countries to developing countries under climate agreement looks much smaller and within the reach of developed countries even after considering their present economic difficulties.

Worst, it is known that these subsidies, paid for by taxpayers, end up deepening inequality and impeding action on climate change, UNDP said. Continuing subsidies on fossil fuels not only makes a mockery of the global efforts to get rid of fossil fuels but also derides the fact that the world continues to spend billions of dollars on fossil fuel subsidies, while promises of finances to the developing countries for action on climate remain grossly unfulfilled.

Secondly, climate finance for investing in clean energy is an opportunity to build a sustainable world with a sustainable market mechanism. Interestingly, the price of renewable energy, like solar energy is falling rapidly. There is a need to develop the economics and social-impact case studies of places like Masdar City, in the UAE; Modhera Village, in India; and Solar Valley, in Dezhou, in the Shandong Province of China, for demonstrating them during COP28, as a source of inspiration to world leaders.

Thirdly, raising fuel prices to their fully efficient levels by reducing subsidies also reduces projected global fossil fuel-related CO2 emissions to 36%, mainly in the developed countries, below baseline levels in 2025 – or 32% below 2018 emissions, as per UNDP. This reduction is in line with the 25-50% reduction in global GHGs below 2018 levels needed by 2030 to be on track with containing global warming to the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5-2 degrees C. Globally, around 74% of the CO2 reduction comes from reduced use of coal, while 21% and three per cent, respectively are from reductions in consumption of petroleum and natural gas.

Fourthly, removal of subsidies has the power to speed up implementation of other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), like reducing inequality (SDG 10), Good Health and Wellbeing (SDG 3), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7) and climate action (SDG 13). H.E. Dr. Al Jabar could consider taking such a holistic and integrated approach to avail the opportunities to link climate solutions to SDGs. His technology and management background could provide proven examples to lead the COP28 negotiations.

Fifthly, phasing out subsidies and using the revenue gain for better targeted social spending, reductions in inefficient taxes, and productive investments can promote sustainable and equitable outcomes. The removal of fossil fuel subsidies would also reduce energy security concerns related to volatile fossil fuel supplies.

There is a need to show that the path to climate finance goes through bold practices rather than through Summits. H.E. Dr. Al Jaber still has a few months to show his ‘Masdar Will’ to win this impasse over finance, otherwise it could turn out to be yet another COP that would end with the usual clichéd headlines.

H.E. Dr. Al Jabar’s moment of truth has arrived. It is strengthened by the climate’s historically unmatched impacts. He is on the threshold of making UAE’s Presidency a lasting success if he gets everyone to act for integrated benefits.

The writer is former Director of UNEP. He is also the Founder-Director, Green TERRE Foundation; Prime Mover, SCCN; and Coordinating Lead Author, IPCC, which won the Nobel Peace Prize. He may be reached at shende.rajendra@gmail.com. He writes exclusively for Climate Control Middle East magazine.

Copyright © 2006-2025 - CPI Industry. All rights reserved.