Focusing his attention on the much-neglected issue of emission by kitchen exhausts, Dr Iyad Al-Attar discusses why air filtration considerations should be included in the decision-making process in this area.

Who wants to wake up to the news that a slew of exhaust-emitting restaurants, a beehive of residential buildings and noisy mechanical workshops would be built across the street from where one lives? A nd what would the community’s reaction be if news spread that a hazardous waste facility, incinerators, garbage dumps or a hospital treating infectious diseases would spring up next door? The predictable and typical reaction would be “Not In My Back Yard!” or NIMBY.

nd what would the community’s reaction be if news spread that a hazardous waste facility, incinerators, garbage dumps or a hospital treating infectious diseases would spring up next door? The predictable and typical reaction would be “Not In My Back Yard!” or NIMBY.

NIMBY

The acronym NIMBY is a pejorative characterisation of opposition by residents to a proposal for a new development in the neighbourhood due to shared concerns [1]. New development, although important, elicit opposition from residents (NIMBYies), as they believe that the projects should be relocated elsewhere.

However, before we accept or reject development projects, we ought to closely examine how they are designed and executed, and what sort of air they would exhaust into the surrounding environment. It is understandable if the community concerns vary. For example, there could be concerns in the case of mushrooming of residential buildings, which would increase the density of population in the neighbourhood, strain public services and the general infrastructure, and cause traffic congestions and/or lower property values. Certainly, one serious concern that must be addressed is the impact on the urban air quality and the role of appropriate air filter selection for air-handling units (AHUs) to provide cleaner air for the indoor space.

An exhausting issue

Cooking, in general, is one of the most significant sources of ultrafine particles [2,3,4]. Several authors have highlighted that exposure to ultrafine particles can impact our DNA, and respiratory and cardiovascular systems [5,6,7]. Ultrafine particles have the propensity to deposit themselves in the human lungs, resulting in inflammation and impairment of the lung cells [8]. Further, inhaled ultrafine particles can be transported from the respiratory system to the blood circulation system and, eventually, to other organs [9].

Cooking, in general, is one of the most significant sources of ultrafine particles [2,3,4]. Several authors have highlighted that exposure to ultrafine particles can impact our DNA, and respiratory and cardiovascular systems [5,6,7]. Ultrafine particles have the propensity to deposit themselves in the human lungs, resulting in inflammation and impairment of the lung cells [8]. Further, inhaled ultrafine particles can be transported from the respiratory system to the blood circulation system and, eventually, to other organs [9].

Let’s consider the construction of a restaurant as an example, which a community may regard as a “no objection” project. Restaurants typically involve considerable amount of deep oil frying and charcoal grilling that emit a great deal of aerosol that contains oil, smoke and other particles. Needless to say, charcoal grills emit deadly carbon monoxide fumes and, undoubtedly, charcoal meat grill workers are subject to it. The questions that emerge here are: Is it acceptable that workers inhale these emissions? By the same token, isn’t it an unfair practice to exhaust such emissions into the atmosphere, in the interest of the local and global environment?

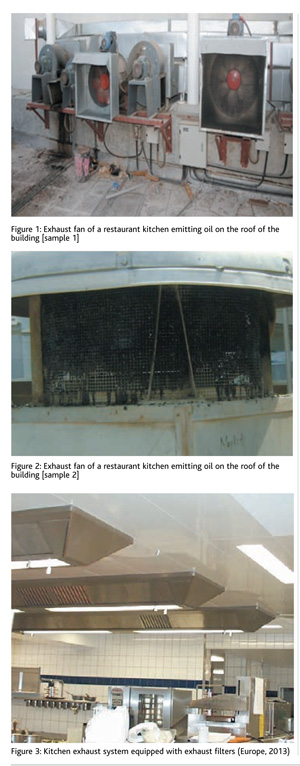

At this point, filtration solutions come to play a critical role. It is evident that they are instrumental in determining whether their performance is efficient enough to allow such restaurants to operate in the neighbourhood without polluting the urban air and exerting excessive load on the filter on the air intake of the AHUs. Examining Figures 1 and 2, which illustrate different GGC examples of exhaust fans of restaurant kitchens emissions oil on the roof of the building, make us ask the following questions:

Figures 3 and 4 bring the functions of kitchen hoods and oil separators to question, the appropriate fan speed relative to the emission concentration, and if it is, in fact, variable to accommodate different emission concentrations?

In a recent trip to Europe, I was impressed to see an exhaust fume hood designed and positioned nearly in the middle of the restaurant in a shopping mall to protect staff members and customers alike. When I investigated further about where the emission was taking place, I was pleased to learn that behind the great removal action were engineering filtration solutions implemented to combat emissions that affected workers, customers and the environment. Figure 5 shows efficient oil separators installed in the kitchen hood, along with a filtration exhaust unit.

In a recent trip to Europe, I was impressed to see an exhaust fume hood designed and positioned nearly in the middle of the restaurant in a shopping mall to protect staff members and customers alike. When I investigated further about where the emission was taking place, I was pleased to learn that behind the great removal action were engineering filtration solutions implemented to combat emissions that affected workers, customers and the environment. Figure 5 shows efficient oil separators installed in the kitchen hood, along with a filtration exhaust unit.

Although people may not lean towards installing a kitchen exhaust hood with an appropriate filtration unit, perhaps owing to lack of knowledge or concerns about noise, several studies have demonstrated that installation and operation of kitchen exhaust hoods can reduce cooking-related pollutants, such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and ultra fine particles [10,11,12,13,14, 15]. Furthermore, the kitchen exhaust hood performance is influenced by several factors:

Not in my AHU

It is certain that kitchen emission, as discussed above, needs to be removed at the earliest stage of the source. Failing to do so, oil droplets and the associated odour would constitute two major problems in altering filter performance. At this point, filter selection may need to be changed to deal with the presence of oil in the air stream and to control the odour invading the building. Exhausting such emission would not be appreciated as it may be reintroduced in the AHUs responsible to providing conditioned air for the indoor space. If we refrain from exhausting kitchen emissions to the urban environment by enforcing intelligent exhaust filtration solutions, reactions and perceptions towards a new construction in the neighbourhood may differ.

It amazes me that we tolerate kitchen exhaust emission into the environment rather than giving it our full attention. In this article, I have addressed the issue of kitchen exhausts which people may regard as harmless. However, if we superimpose our discussion on dealing with exhaust of hazardous waste facilities, incinerators, garbage dumps, or hospitals treating infectious diseases, wouldn’t we all end up becoming NIMBYies?

The desire to dream

There is no question that our planet needs attention and care. More importantly, we need to spare a thought about how to be environmentally responsible. Frankly speaking, unless we put a price tag for damaging our environment, little can be achieved towards making people environmentally responsible. If we really like our children to inherit our principles, shouldn’t we be instigating these price tags in the first place? If we would like to leave behind a healthier planet, shouldn’t we control and regulate emissions into it? If we ought to lead change, shouldn’t we believe that even if we do not fully succeed in every environmental endeavour we undertake, we need to at least get busy trying? Finally, if the Earth were to speak, it would definitely say: “NOT IN MY PLANET!”

Dr Iyad Al-Attar is an Air Filtration Consultant. He can be contacted at: iyad@iyadalattar.com

References

NOTE: Unless otherwise referenced, the images used in this article are copyright of the author.

Copyright © 2006-2025 - CPI Industry. All rights reserved.